For Russian liberals the late opposition leader Alexei Navalny was a glimmering hope for a future of democracy. For many Ukrainians, particularly in the context after a decade-long war, he was more complex, casting doubts on whether Russian opposition towards Vladimir Putin was necessarily aligned to support for Ukraine’s full independence.

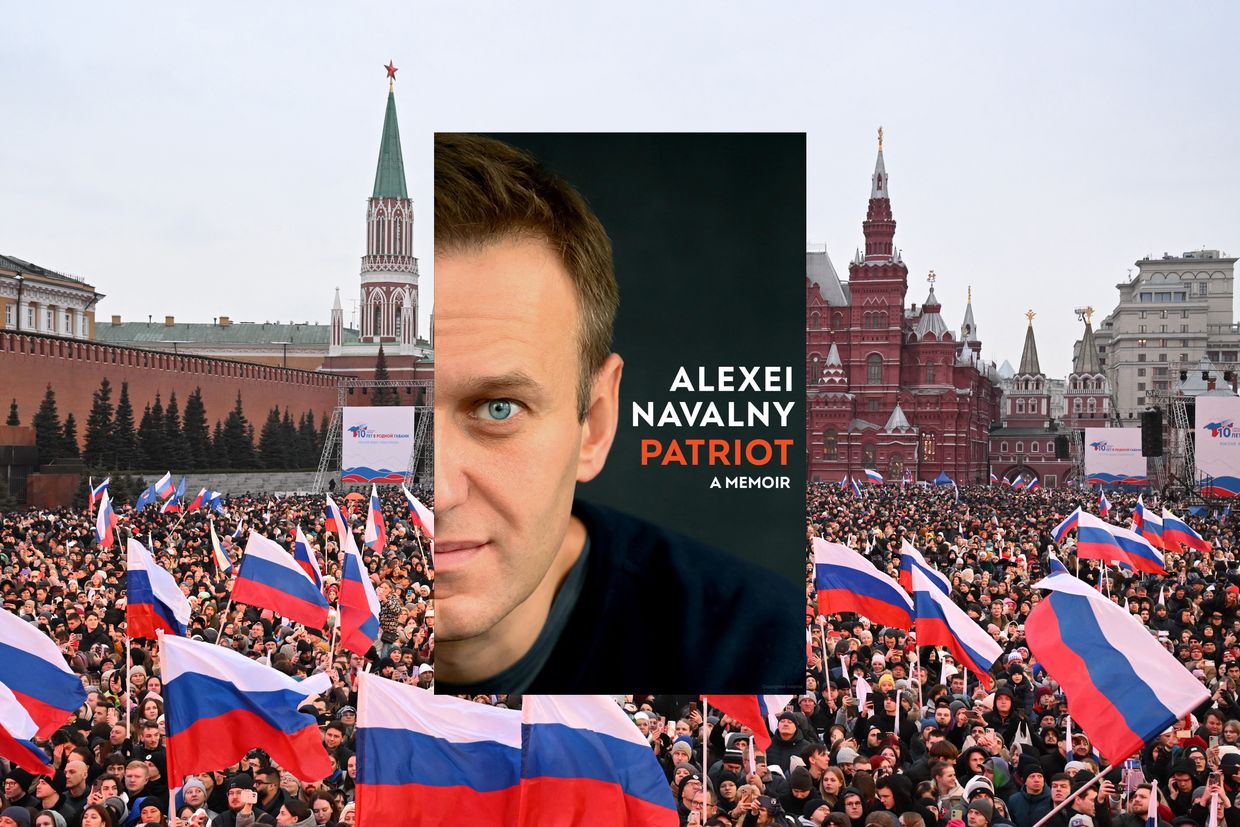

The English translation of Navalny’s “Patriot” was released in October 22. He began writing it in Germany in 2020 after recovering from a Novichok poisoning and continued to write during his imprisonment, smuggling the notebooks out through his lawyers. The publication of the book has brought new praise for the former opposition leader who died in one of Russia’s notorious penal colonies on February 16. Yulia Navarnaya has been on an extensive U.S. media tour. Rachel Maddow and other pundits have already hailed her as the last hope for a democratic Russia.

Navalny returned home to Russia in 2021, after he recovered from his poisoning. He was arrested at the airport and a Kafkaesque series of fabricated court proceedings was brought against him. The authorities also tried to break his spirit.

Navalny, from prison, condemned the full-scale conflict against Ukraine, and acknowledged that it was unprovoked. He challenged Putin’s narrative, which justifies the aggression by claiming NATO expansion and the necessity to protect Russia’s’sphere of influence’. Navalny’s disdain for the Russian state media was especially evident in “Patriot,” where he wrote how they distorted the truth and tried to rewrite it as a fabricated tragedy.

Navalny used words such as “fratricidal,” and wrote, “The reasons for it are the political and economical problems within Russia, Putin’s desire to retain power at all costs, and his obsession to his own historical legacy.” This ignores the genocidal intention behind the war, including the destruction of Ukrainian culture sites, the forced removal of thousands of Ukrainians children to Russia, or the “re-education” program implemented by occupation authorities.

Putin has repeatedly shown how his tenuous grasp of historical events has influenced the motivation behind his decision to launch a full scale war against Ukraine. For example, he claimed that Ukraine’s claim for sovereignty was not legitimate because it had been “invented by the Bolsheviks”. In his article, “On the Historical Unity of Ukrainians & Russians,” published in 2021 by the Russian autocrat Putin, he claimed that Ukrainians & Russians were “one nation, a single entire.” For the Russian authoritarian, his legacy is the forced reunifications of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. Navalny’s view that the war can be reduced to issues such as politics and corruption is not accurate.

Navalny’s reflections on 2014 in “Patriot”, a book he wrote, omit the Russian invasion of Ukraine’s Donetsk Oblast and Luhansk Oblast. The former opposition leader referred to the illegal annexation in several passages but never stated that it had been taken from Ukraine. This stylistic choice will no doubt confuse readers familiar with his controversial comments from previous years including “Crimea belongs to those who live in Crimea” and his quip saying that it wasn’t “a sandwich that can be passed back and fourth between the two nations.” Navalny did finally acknowledge from prison, after the start of the full-scale conflict, that Ukraine’s borders of 1991 should be respected. This would mean the return to Crimea.

Navalny is not afraid to criticize the Soviet failures. He writes in his memoir, “a state that cannot produce enough milk for its people does not deserve my nostalgic feelings,” a reference the food shortages during communist rule. He devotes several passages in his book “Patriot,” to the poor handling the Chornobyl Nuclear Disaster and the Soviet-Afghan War from 1979-1989. He writes that both events “dug a grave for the USSR.”

He is only able to mention historical injustices against non-Russians, including Ukrainians, through an anecdote he heard from his grandmother when he was a child and asked her why she hated Lenin. She told him that her family had avoided being deported to Siberia but their wealth was taken away by the implementation of collective agriculture. According to family legend, the iron roof of the family house, which was “the envy” of the entire village, was sold and the money spent on “drink in the village council.”

“I didn’t believe that bit of the story at the time,” Navalny said, “but I now have no doubts it was true.” Out of respect for her, I never brought up Lenin.

Navalny also remembered being shocked when he was a child and his Ukrainian relatives thought it was funny to joke that they would spit on Vladimir Lenin, after a cousin was brought in to see the embalmed corpse of the Bolshevik Leader in Moscow. They had been taught during Soviet times that Lenin was “sacrosanct.”

His memories of his childhood summers spent in Zalissia – a village just two hours away from Chornobyl – in Kyiv Oblast are a good example of Russian stereotypes about Ukrainians. For instance, his relatives would “tut tut” about how thin and pale he was, and how they had to “fatten him up with good Ukrainian lard.”

After spending summers as a child with his Ukrainian relatives, Navalny was asked whether he identified himself more as Ukrainian or Russian. He wrote that he “did his best to avoid giving a straight answer,” because answering such a question would be “like asking who you love more, your father or mother, which is impossible to answer.”

Tensions between Ukrainians, and the Russian opposition have been high over the last decade of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Nearly three years after the start of the full-scale conflict, prominent figures such as Vladimir Kara-Murza, Ilya Yashin and others who were released by the U.S. in an exchange of prisoners with Russia this summer continue to refer to the war as “Putin’s war.” Many argue that this framing absolves Russians of their involvement in the conflict which has claimed tens of thousand of Ukrainian lives and displaced millions.

In an address to the Bled Strategic forum in Slovenia, Navalnaya criticized those who pushed for a renewed push to “decolonize Russia”, saying that those who advocated for it “cannot explain why people with common backgrounds and cultures should be artificially separated.” This statement is a glaring oversight of the systemic discrimination and cultural ostracization that have existed for more than 190 minorities who call Russia home. Navalny wrote in his memoirs that his wife has “even more radical views” than he does, but he didn’t elaborate.

The Russian opposition has found it easier to bring attention to issues such as widespread corruption. In “Patriot,” Navalny argued the corruption of the Russian state, which has plunged many of his fellow Russian citizens into poverty, is one of the most deeply-rooted obstacles to the country becoming “a normal, rich, governed by law country.”

Navalny has made a number of controversial statements over the years that have raised concerns among Ukrainians about how the Russian opposition views relations with Ukraine differently than Putin’s regime. Navalny was shocked by the Orthodox Church of Ukraine’s autocephaly, which established it as a separate religious body from Moscow. He wrote that the Russian Orthodox Church would lose up to half of their ‘living parishes’. In just four years, Putin and his idiots destroyed what took centuries to build. Putin is the enemy to the “Russian world.”

The term “Russian World” promotes the notion that Russian-speaking people around the world, regardless of where they are from, are connected through cultural, linguistic and historical ties. Similar concepts are found in other imperial contexts. However, Russia’s framing has taken on a militaristic tone over the past few years. This aggressive stance has put at risk the sovereignty of countries like Moldova and Georgia, as well as Ukraine.

In “Patriot,” Navalny admitted in “Patriot” that he was concerned about the “plight of Russians” after the dissolution of USSR. He criticized Putin’s government for “talking endlessly about oppressed Russians who live as minorities overseas following the dissolution countries that made up USSR while doing nothing to assist them.” He also advocated for funding Russian schools abroad to spread the Russian language, and even “resettling the people back to their home country.”

How did Navalny’s views about Ukraine-Russia relations change during his prison sentence? It was encouraging that he recognized Crimea as Ukraine and called for reparations after the regime change in Russia. He also called for an international investigation of Russian war crimes in Ukraine. Would he have seen Ukrainians’ remembrance of their language and culture as a threat against the prosperity of so-called “Russian World”? His concern for the economic prosperity of Russia and his condemnation of a full-scale conflict suggest that our current reality might have been avoided if he could have formed a strong political movement to overthrow Putin. Yet, given that he was concerned about “the plight” of Russians and described both countries “fraternal,” tensions between them would have undoubtedly taken a different form.

In light of all this, the use of Russian transliteration to describe Ukrainian locations is one of the most shocking and disappointing aspects of this memoir. Kyiv, Chornobyl and Zalissia are all rendered as “Kiev”, which is not only outdated but also careless. This is a mistake made by the translators Arch Tait, Stephen Dalziel and Alfred A. Knopf a subsidiary to Penguin.

The future trajectory of Navalny’s evolving views on Ukraine-Russian relations will always remain speculative. Navalny, despite any valid criticisms leveled at him, should not have been imprisoned, poisoned, or killed in custody. In a perfect world, the political opposition in Russia would flourish, creating a healthy democratic atmosphere. His life’s works is proof that, despite the overwhelming odds facing those who live in an authoritarian regime, it is never too early to fight for a more democratic future. It is admirable that he managed to smuggle the last passages of the book out through his lawyers, and in this way, remain defiant to Putin until the very end.

Navalny’s one-year death anniversary is fast approaching. The remaining figures of the Russian opposition, who are in exile and engaged in squabbles with each other, lack a clear strategy for taking on Putin. Many condemn the war but are hesitant to discuss collective guilt. The decade-long aggression against Ukraine is the greatest moral failure of Russian society. More than 145,000 war crime investigations by Ukraine’s Prosecutor General’s Office prove this.

If there is any hope for a democratic Russia it must start with those who will continue Navalny’s work acknowledging that Ukraine’s military victory over Russia was the key to a democratic future for their own country. In an interview with German media, Navalny’s widow said that it is “hard to say,” whether it is right to arm Ukraine since “the bombs hit Russians”. Many of the remaining opposition members cannot move beyond calling it “Putin’s war” and the prospect of a democratic Russia remains difficult to imagine.

Note from the Author:

Kate Tsurkan here, thank you for reading my book review. I hope that my recommendations will be helpful to you on your next visit to the bookstore. Please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent if you enjoy reading about such topics.

Kate Tsurkan, a reporter for the Kyiv Independent, writes mainly about cultural topics. Her writings and translations were published in The New Yorker and Harpers, The Washington Post and The New York Times. She is also the co-founder and editor of Apofenie Magazine.

Read More @ kyivindependent.com